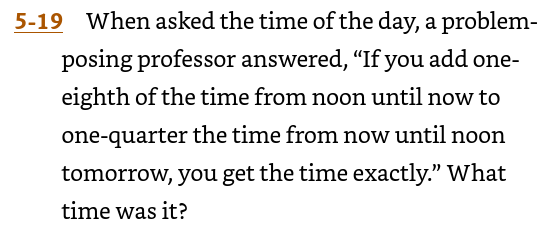

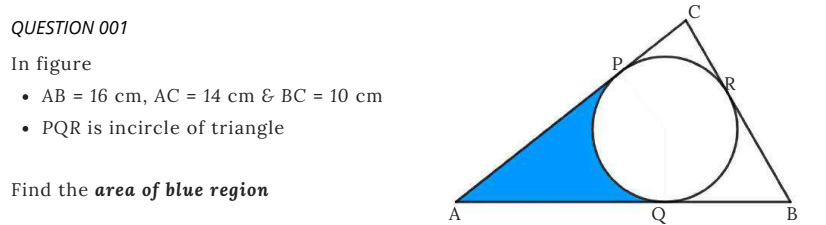

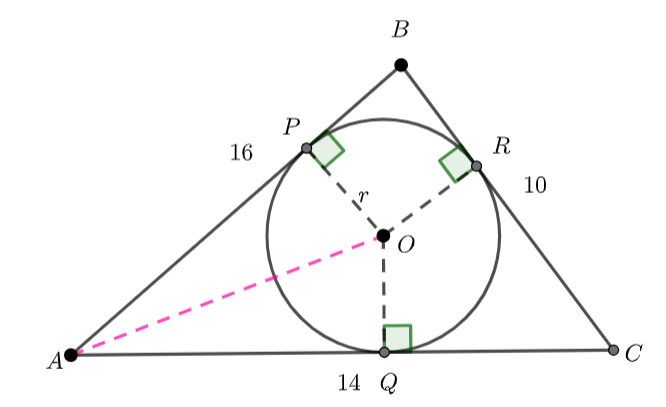

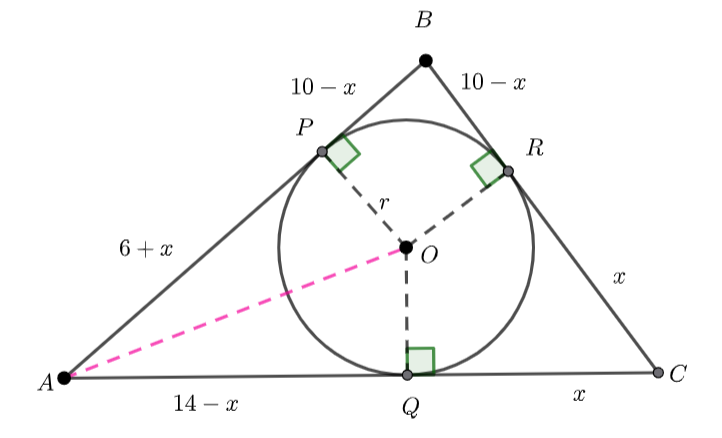

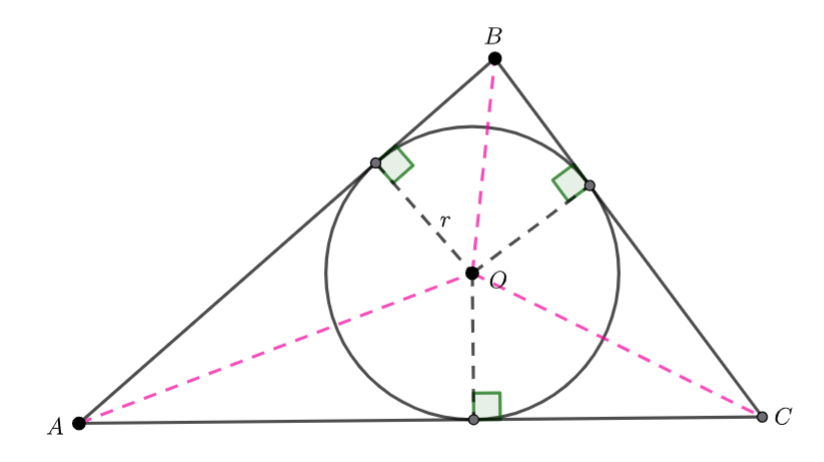

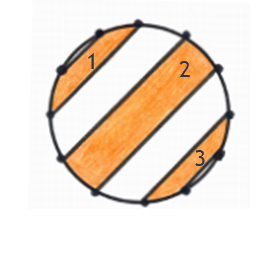

Band ![]() and

and ![]() have the same area.

have the same area.

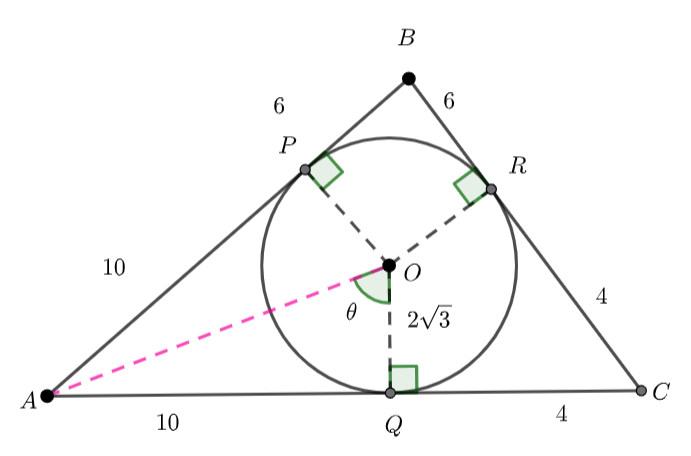

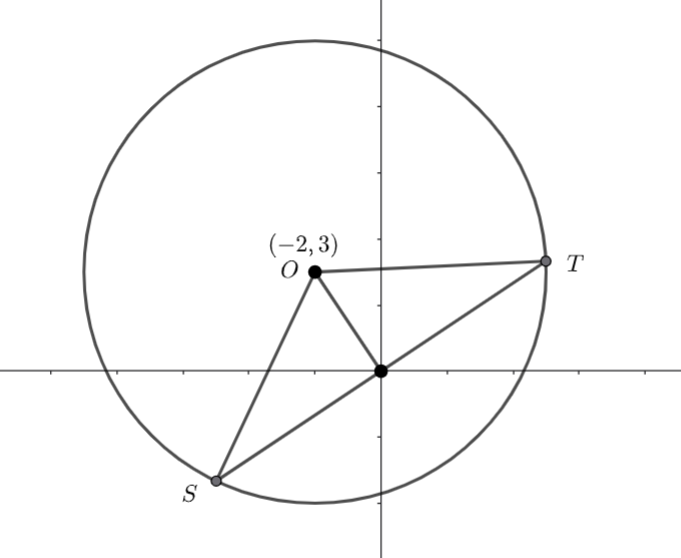

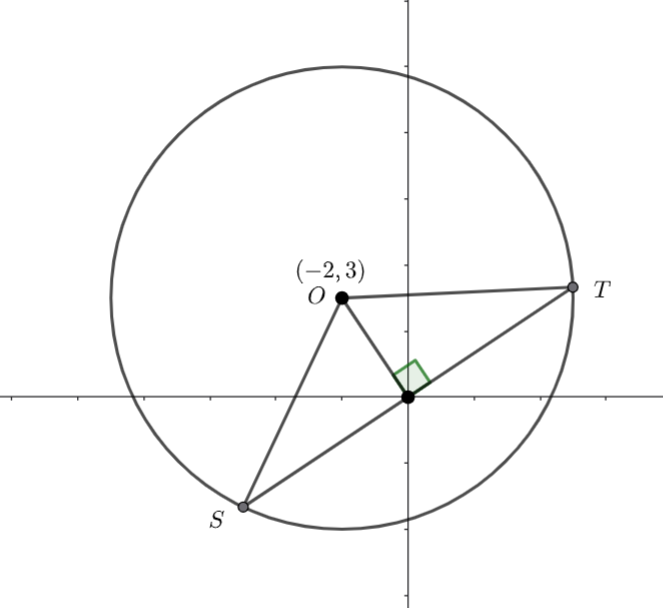

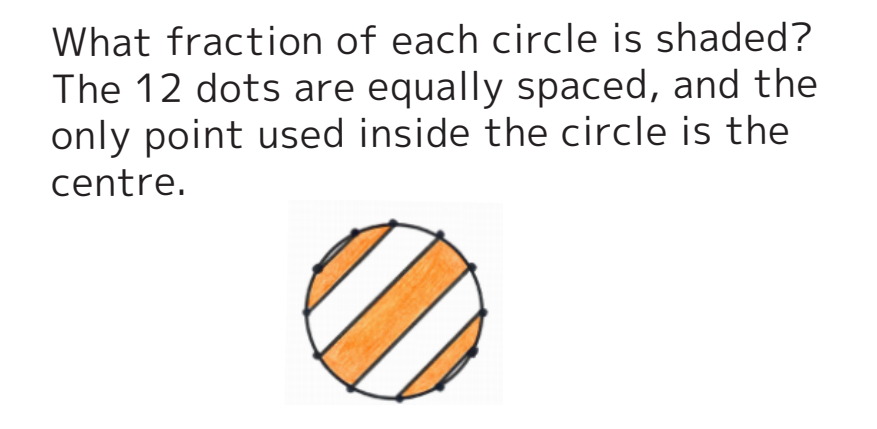

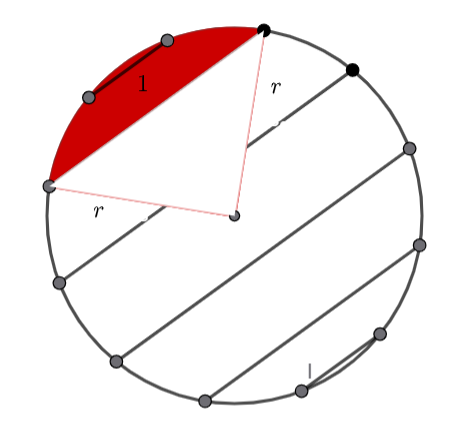

We want to find the area of the shaded segment.

As the dots are equally spaced, the sector’s angle is ![]()

Remember the area of a segment is ![]() where the angle measurement is in radians.

where the angle measurement is in radians.

(1) ![]()

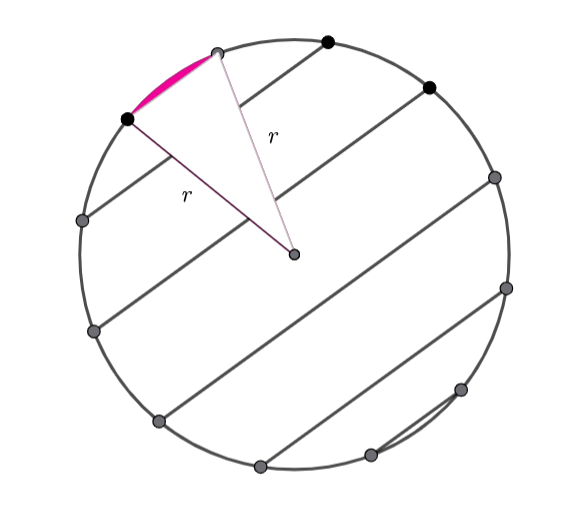

We want to find the area of the shaded segment.

As the dots are equally spaced, the sector’s angle is ![]()

(2) ![]()

The area of band ![]() is equation

is equation ![]() equation

equation ![]() .

.

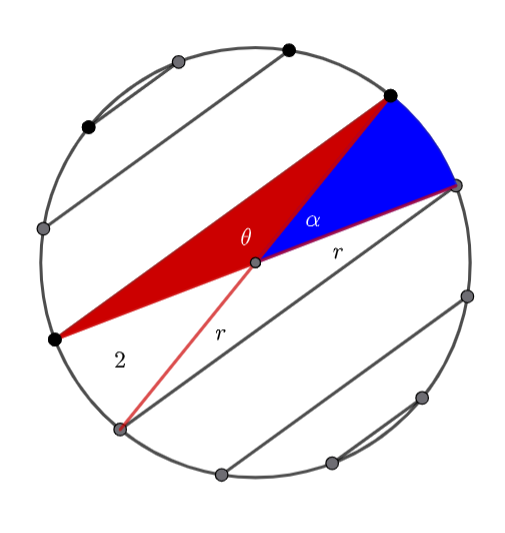

(3) ![]()

Band 2 consists of two congruent triangles and two congruent sectors.

![]()

(4) ![]()

Hence the shaded area is ![]()

The area of the circle is ![]()

Hence the fraction of the shaded area is ![]()