Solve  for

for

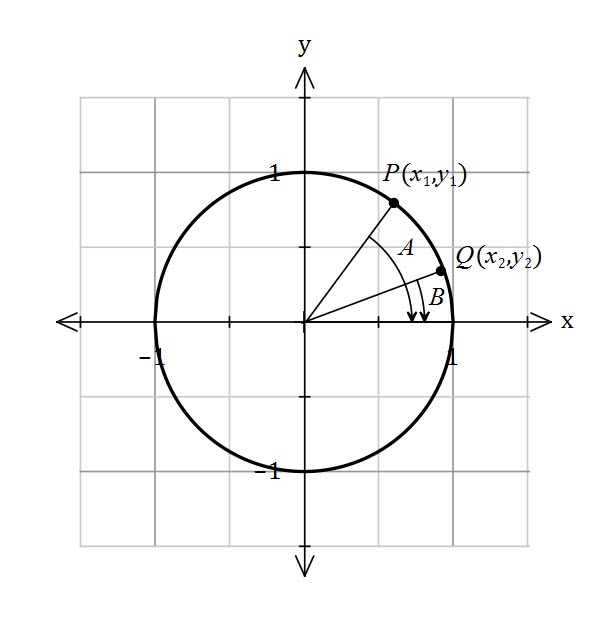

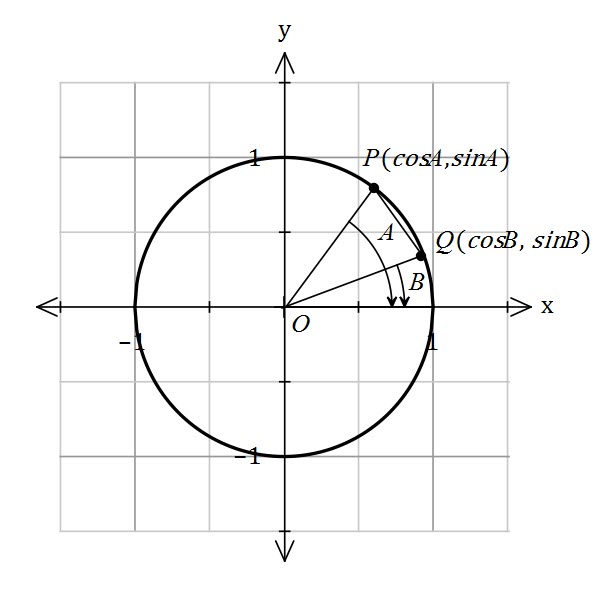

Sine is positive in the first and second quadrants.

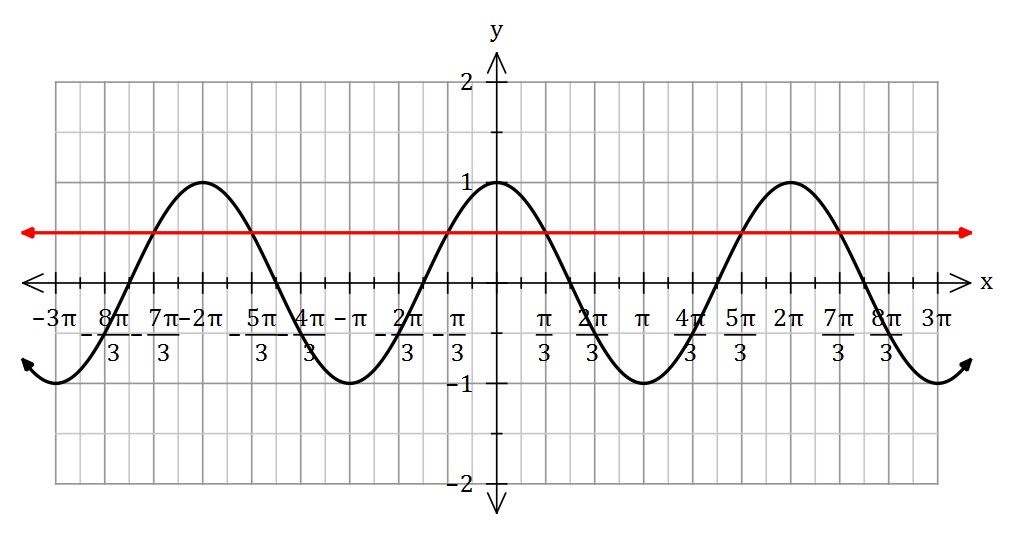

But what if we aren’t given a domain for the  values?

values?

Then we need to give general solutions.

For example,

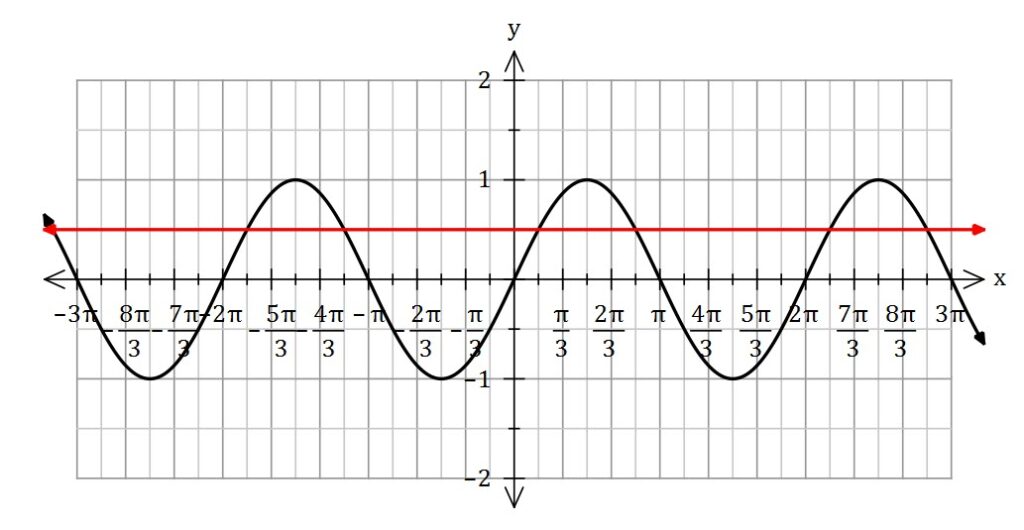

Solve

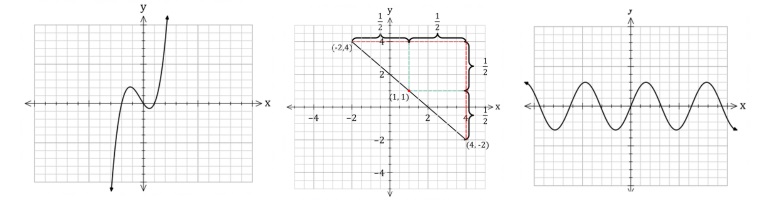

As you can see from the sketch above, there are infinite solutions.

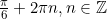

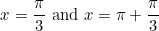

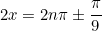

The sine function has a period of  , and so if

, and so if  is a solution then

is a solution then  is also a solution. This means

is also a solution. This means  is a general solution. And we can do the same for the second solution

is a general solution. And we can do the same for the second solution  .

.

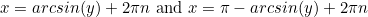

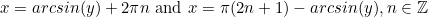

In general

We can turn this into one equation

What about cosine?

Solve

Cosine is positive in the first and fourth quadrants (it also has a period of  . The first two (positive) solutions are

. The first two (positive) solutions are  and

and  .

.

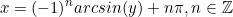

To generalise,  , which we can make into one equation

, which we can make into one equation

In general

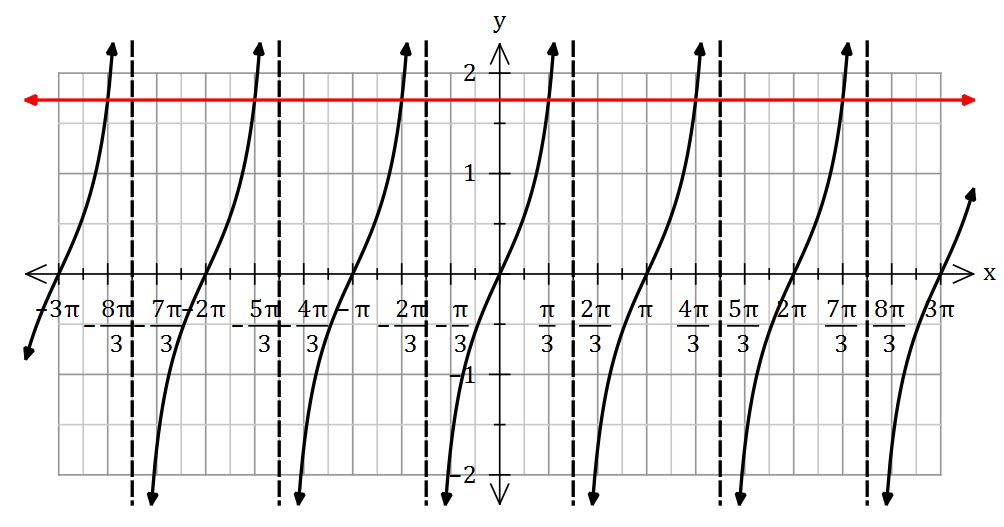

What about the tangent function? Remember tan has a period of  .

.

Solve

First, note that the solutions are all a common distance ( ) apart.

) apart.

Tan is positive in the first and the third quadrant

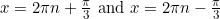

Because all of the solutions are  radians apart, the general solution is

radians apart, the general solution is

In general

Examples

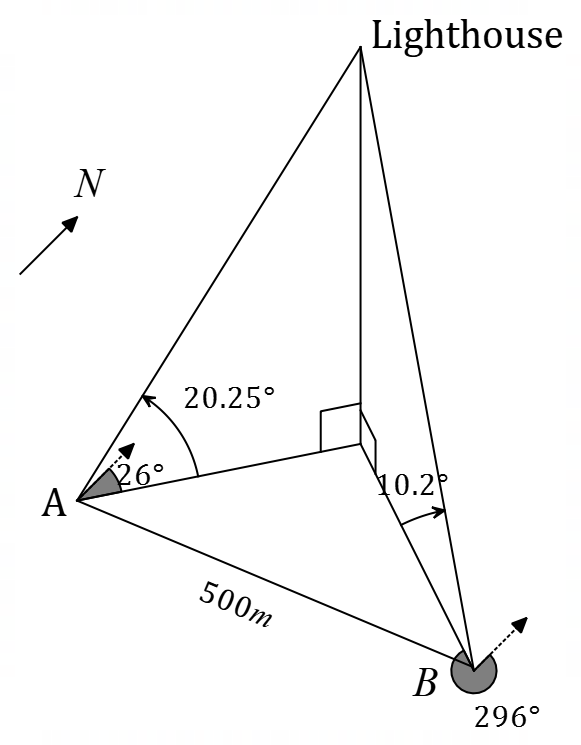

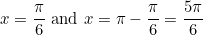

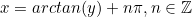

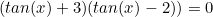

Solve for all values of  ,

,

This is a quadratic equation – we need two numbers that add to  and multiple to

and multiple to  ,

,

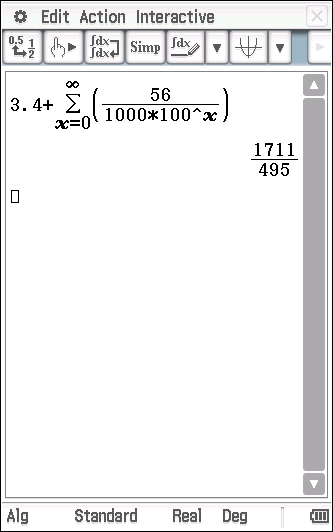

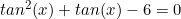

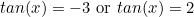

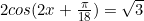

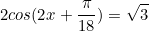

Solve

![]()

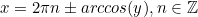

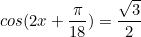

![]() is either

is either ![]() or

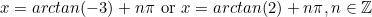

or ![]() .

. ![]() as

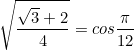

as ![]() as there are exact values for

as there are exact values for ![]()

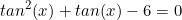

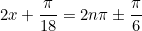

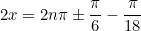

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() is in the first quadrant, we don’t need to consider the negative version.

is in the first quadrant, we don’t need to consider the negative version.![]()