I usually choose to use synthetic division when factorising polynomials, but I know some teachers are unhappy when their students do this. So for completeness, here is my PDF for Polynomial Long Division.

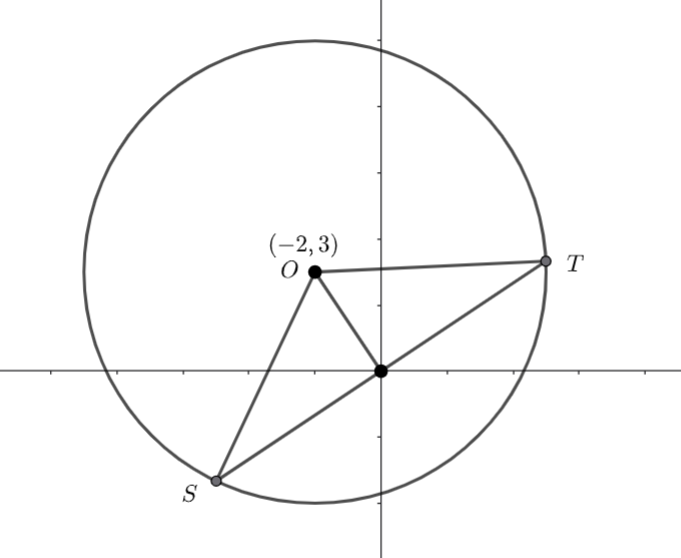

Geometry Circle Question

In the diagram below, ![]() and

and ![]() lie on the circle with centre

lie on the circle with centre ![]() . If

. If ![]() and

and ![]() , determine with reasoning

, determine with reasoning ![]() and

and ![]()

We know ![]() – radii of the circle.

– radii of the circle.

Which means, ![]() is isosceles and

is isosceles and ![]() – equal angles isosceles triangle.

– equal angles isosceles triangle.

![]() – angle at the centre twice the angle at the circumference.

– angle at the centre twice the angle at the circumference.

![]()

This means ![]() – angles on a straight line are supplementary

– angles on a straight line are supplementary

![]() – equal angles isosceles triangle and the angle sum of a triangle.

– equal angles isosceles triangle and the angle sum of a triangle.

![]() – angle at the circumference subtended by the same arc are congruent.

– angle at the circumference subtended by the same arc are congruent.

![]() – angles at the circumference subtended by the same arc are congruent.

– angles at the circumference subtended by the same arc are congruent.

![]() – equal angle isosceles triangle

– equal angle isosceles triangle

Hence ![]()

Completing the Square

Completing the square is useful to

- sketch parabolas.

- solve quadratics.

- factorising quadratics

- finding the centre and radius version of the equation of a circle.

When completing the square we take advantage of perfect squares. For example, ![]()

![]() and

and ![]()

Example 1

Put ![]() into completed square form.

into completed square form.

What perfect square has an ![]() term?

term?

![]()

We don’t want ![]() , we want

, we want ![]() , so subtract

, so subtract ![]()

![]()

![]()

What about a non-monic quadratic? For example,

![]()

Factorise the ![]()

![]()

And continue as before

![]()

Example 2

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

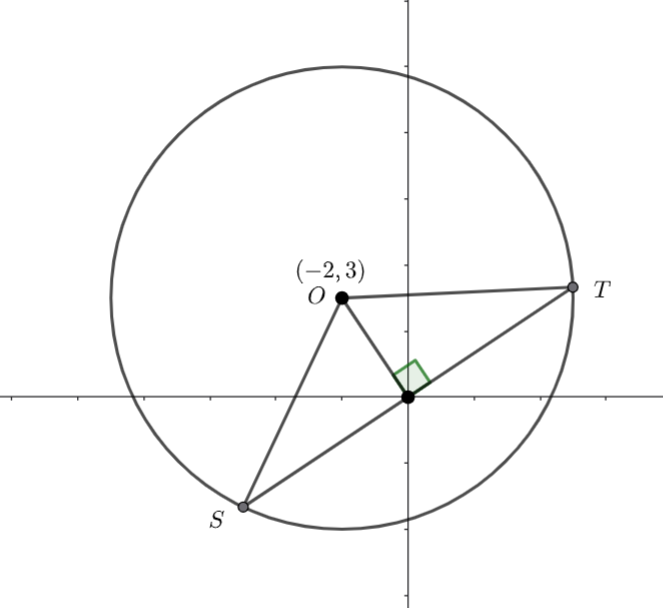

Equation of a Circle and Geometry Question

A circle has equation

(a) Find the centre and radius of the circle.

Pointsand

lie on the circle such that the origin is the midpoint of

.

(b) Show thathas a length of 12.

(a)We need to put the circle equation into completed square form

![]()

![]()

The centre is ![]() and the radius is

and the radius is ![]() .

.

(b)Draw a diagram

We know ![]() and

and ![]() are radii of the circle. Hence

are radii of the circle. Hence ![]() is isosceles and the line segment from

is isosceles and the line segment from ![]() to the origin is perpendicular to

to the origin is perpendicular to ![]() .

.

![]() and the distance from

and the distance from ![]() to the origin is

to the origin is

![]()

We can use Pythagoras to find the distance from the origin to ![]() .

.

![]()

Hence ![]()

Integration Question (much easier with Integration by Parts)

The Year 12 Mathematics Methods course doesn’t cover Integration by Parts, so they end up with questions like the following.

Determine the following:

(a)

(b)

Hence, determine the following integral by considering both parts (a) and (b)

(a) Use the product rule

(1) ![]()

(b)

(2) ![]()

I need to use equations ![]() and

and ![]() to find

to find ![]() .

.

The ![]() terms need to vanish and I need

terms need to vanish and I need ![]() of the

of the ![]() terms.

terms.

![]()

(3) ![]()

(4) ![]()

Equation ![]() plus equation

plus equation ![]()

(5) ![]()

Integrate both sides of the equation

![]()

By the fundamental theorem of calculus, we know

![]()

![]()

![]()

Integration by Parts

Remember ![]()

![]()

Let ![]() , then

, then ![]()

and ![]() , then

, then ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Let ![]() , then

, then ![]()

and ![]() . then

. then ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Collect like terms (the integrals are like)

![]()

![]()

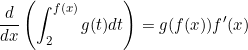

Fundamental Theorem of Calculus

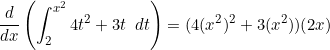

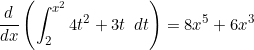

(1)

My Year 12 Mathematics Methods students are getting ready for their exam, and questions using the above idea have created a bit of consternation. I am going to work through an example, and show why the ‘formula’ works.

Example

Find

.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(2) ![]()

If we used ‘formula’ ![]()

(3)

We can see equation ![]() and

and ![]() are the same.

are the same.

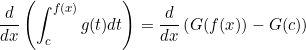

More formally

Remember ![]()

![]()

Hard Equation Solving Question

Find the value(s) of ![]() such that the equation below has two numerically equal but opposite sign solutions (e.g.

such that the equation below has two numerically equal but opposite sign solutions (e.g. ![]() and

and ![]() ).

).

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

For there to be two numerically equal but opposite sign solutions, the ![]() term of the quadratic equation must be

term of the quadratic equation must be ![]() .

.

![]()

Hence ![]() .

.

When ![]() the equation becomes

the equation becomes

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Filed under Algebra, Polynomials, Quadratic, Quadratics, Solving, Solving, Solving Equations

Trigonometric Exact Values

Find exactly ![]()

We must be able to find an arithmetic combination of the exact values we knew to find ![]() .

.

![]()

![]()

I re-arranged as above, so I could take advantage of ![]() and

and ![]()

| Useful identities |

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Hence,

![]()

![]()

![]()

Use the quadratic equation formula

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

As ![]() ,

, ![]()

Converting base 10 numbers to base 2

Converting integers to base 2 is reasonably easy.

For example, what is 82 in base 2?

Think about powers of 2

Make ![]() the sum of powers of

the sum of powers of ![]() .

.

![]()

We follow the same approach for real numbers

Convert ![]() to base

to base ![]()

![]() the first number is 1

the first number is 1

![]() the second number is 1

the second number is 1

![]() the third number is 0

the third number is 0

![]() the fourth number is 0

the fourth number is 0

![]() the fifth number is 0

the fifth number is 0

![]() the sixth number is 1 and we have finished

the sixth number is 1 and we have finished

![]()

What about something like ![]() ?

?

The non-decimal part ![]()

![]() first number is zero

first number is zero

![]() second number is 1

second number is 1

![]() third number is 1

third number is 1

![]() fourth number is 1

fourth number is 1

![]() fifth number is 0

fifth number is 0

![]() sixth number is 0

sixth number is 0

We are back to where we started, so ![]()

Filed under Arithmetic, Decimals, Fractions, Number Bases