I usually choose to use synthetic division when factorising polynomials, but I know some teachers are unhappy when their students do this. So for completeness, here is my PDF for Polynomial Long Division.

Category Archives: Year 11 Mathematical Methods

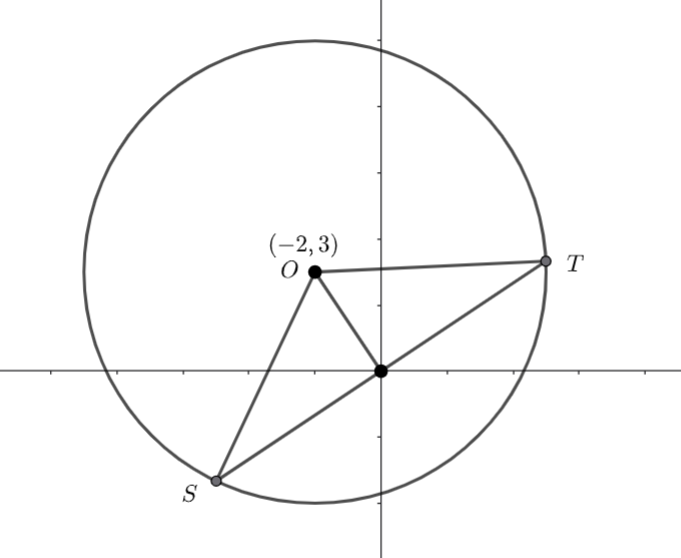

Equation of a Circle and Geometry Question

A circle has equation

(a) Find the centre and radius of the circle.

Pointsand

lie on the circle such that the origin is the midpoint of

.

(b) Show thathas a length of 12.

(a)We need to put the circle equation into completed square form

![]()

![]()

The centre is ![]() and the radius is

and the radius is ![]() .

.

(b)Draw a diagram

We know ![]() and

and ![]() are radii of the circle. Hence

are radii of the circle. Hence ![]() is isosceles and the line segment from

is isosceles and the line segment from ![]() to the origin is perpendicular to

to the origin is perpendicular to ![]() .

.

![]() and the distance from

and the distance from ![]() to the origin is

to the origin is

![]()

We can use Pythagoras to find the distance from the origin to ![]() .

.

![]()

Hence ![]()

Deriving the sum formula for an Arithmetic Progression

Arithmetic progressions (or arithmetic sequences) are sequences with a common difference (i.e. the same number is added or subtracted to get the next number in the sequence).

For example,

![]()

or

![]()

The ![]() term of an arithmetic progression is

term of an arithmetic progression is ![]() where

where ![]() is the first term and

is the first term and ![]() is the common difference.

is the common difference.

i.e. For the sequence above, ![]()

An arithmetic series is the sum of the arithmetic progression.

For example, if the sequence is

![]()

then ![]()

The series is also a sequence and we are going to find the general term, ![]() .

.

![]()

which we can write as

![]()

Now, I am going to write that in reverse order (to make the next bit more obvious)

![]()

I am going to add the two versions of ![]() together

together

Each term has an ![]() and there are

and there are ![]() terms, so we now have

terms, so we now have ![]() . The

. The ![]() terms, we going to group together

terms, we going to group together

![]()

Which simplifies to ![]() and we have

and we have ![]()

![]() terms. So this part of the sum is

terms. So this part of the sum is ![]()

Thus we have

![]()

Which simplifies to

(1) ![]()

Let’s test it, remember the sequence ![]() . We know

. We know ![]()

![]()

Filed under Algebra, Arithmetic, Sequences, Year 11 Mathematical Methods

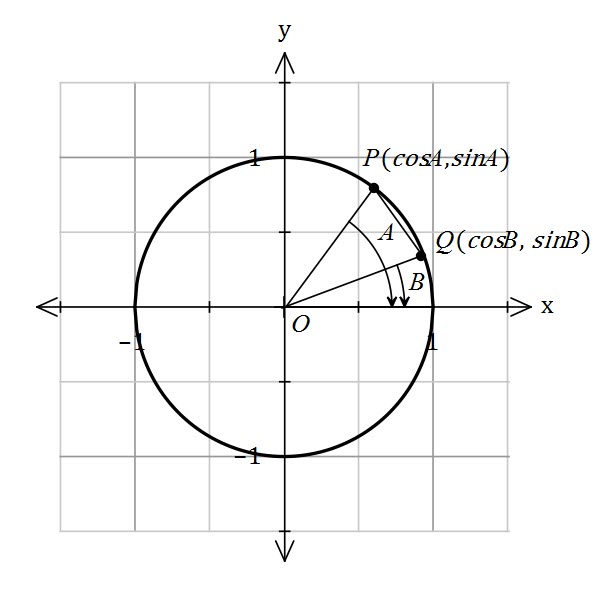

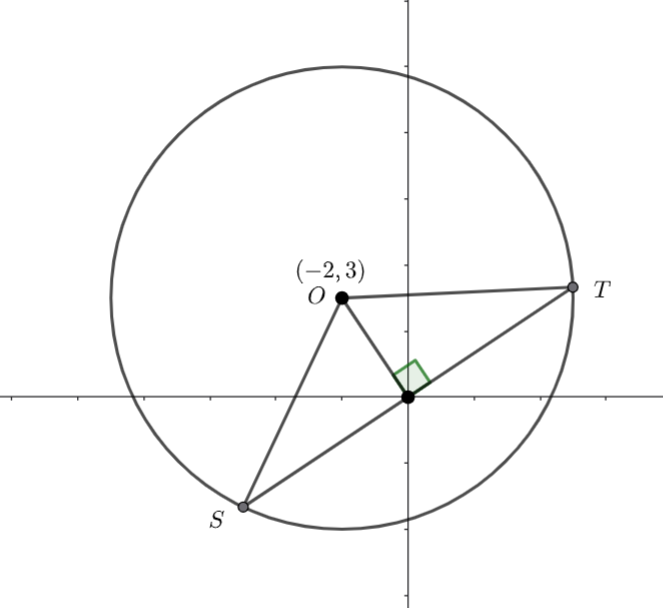

Trigonometric Exact Value

Using an appropriate double angle identity, find the exact value of

The double angle identity for sine is

(1) ![]()

That means ![]() is either

is either ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

It must be ![]() as

as ![]() as there are exact values for

as there are exact values for ![]()

Hence,

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

As ![]() is in the first quadrant, we don’t need to consider the negative version.

is in the first quadrant, we don’t need to consider the negative version.

![]()

Filed under Algebra, Identities, Trigonometry, Year 11 Mathematical Methods

Closest Approach (Shortest Distance) e-activity (Casio Classpad)

At 1pm, object

travelling with constant velocity

km/h is sighted at the point with position vector

km. At 2pm object

travelling with constant velocity

km/h is sighted at the point with position vector

km. Determine the minimum distance between

and

and when this occurs.

OT Lee Mathematics Specialist Year 11 Unit 1 and 2 Exercise 10.1 Question 6.

(1) ![]()

(2) ![]()

![]() is the position vector of

is the position vector of ![]() at 1pm.

at 1pm.

Find the relative displacement of ![]() to

to ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Find the relative velocity of ![]() to

to ![]()

![]()

The relative displacement is perpendicular to the relative velocity at the closest approach.

That is

(3) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Substitute ![]() into the relative displacement and find the magnitude.

into the relative displacement and find the magnitude.

![]()

![]()

![]()

The closest objects ![]() and

and ![]() get to each other is

get to each other is ![]() km at 1:27pm.

km at 1:27pm.

I have made an e-activity for this.

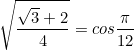

Combinations Proof

Prove ![]()

Let’s start with the right hand side.

![]()

![]()

Simplify

![]()

There is a common denominator of ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

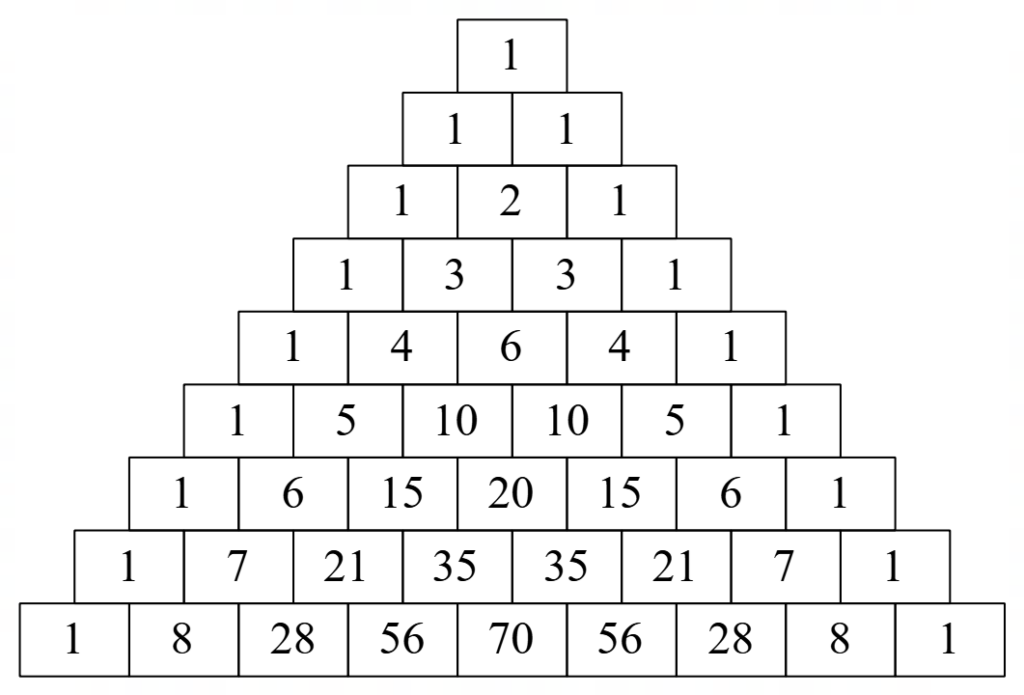

We know this intuitively from Pascal’s triangle

Where each entry is the sum of the two entries above it – for example,

![]()

Remember, Pascal’s triangle can be written as combinations,

so ![]()

Area of Regular Polygons

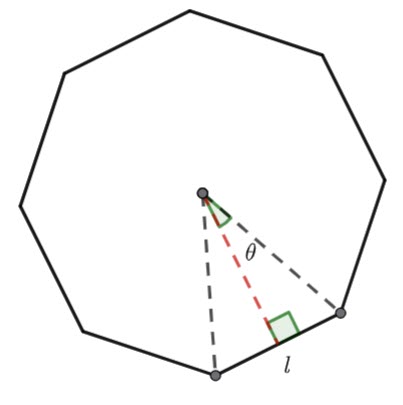

Finding the area of a regular polygon when you know the side length

Find the area of an ![]() sided regular polygon if you know the side length,

sided regular polygon if you know the side length, ![]() .

.

Find the ![]() of the triangle in terms of

of the triangle in terms of ![]() and theta.

and theta.

![]()

![]()

Remember the area of a triangle is ![]()

Hence, ![]()

And ![]()

Therefore ![]()

There are ![]() triangles in an

triangles in an ![]() sided polygon

sided polygon

(1) ![]()

| Find the area of a hexagon with side length 10cm. |

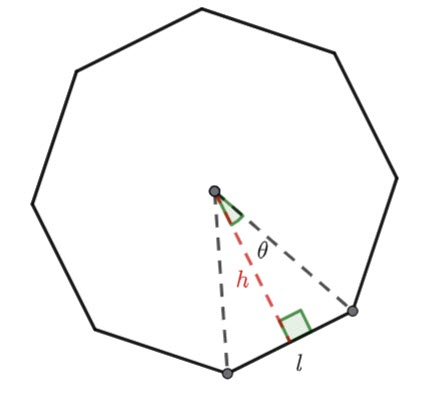

Finding the area of a polygon if you know the inradius or the apothem

The apothem and the inradius are the same. It is the radius of the incircle.

Find the area of the triangle in terms of ![]() and theta.

and theta.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

And ![]()

Hence for an ![]() sided polygon

sided polygon

(2) ![]()

| Find the area of a regular pentagon with apothem 4.5cm |

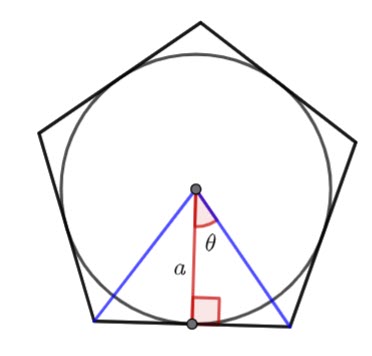

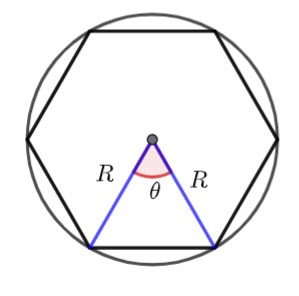

Finding the area of a regular polygon given the circumradius

The circumradius is the radius of the circumscribed circle (![]() in the diagram above)

in the diagram above)

Remember the area of triangle formula

![]()

![]()

![]()

Hence, ![]()

Hence, for an ![]() sided polygon

sided polygon

(3) ![]()

| Find the area of a regular octagon inscribed in a circle of radius 10cm. |

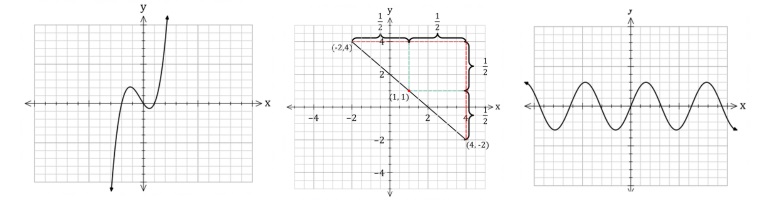

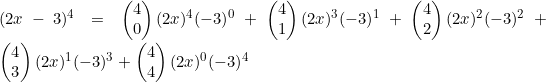

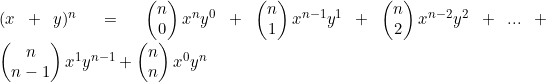

Binomial Expansion Theorem

My Year 11 Mathematics Methods students are working on the Binomial Expansion Theorem.

But before we get onto that, remember Pascal’s triangle

Now we can use combinations to find the numbers in each row. For example, ![]() is

is ![]()

| Expression | Expansion | Co-efficients |

As you can see, the coefficients are the row of pascal’s triangle corresponding to the power. So ![]() would have co-efficients from the sixth row of the table

would have co-efficients from the sixth row of the table ![]() .

.

To generalise

Which we can condense to

![]()

Worked Examples

![]() Expand

Expand ![]()

![]() Find the co-efficient of the

Find the co-efficient of the ![]() term in the expansion of

term in the expansion of ![]() .

.

Remember

, the

is when

![]() Find the constant term in the expansion of

Find the constant term in the expansion of ![]()

We need to find the term where the

‘s cancel out. Each term is

.

.

We need, hence

Therefore, the co-efficient is

Arithmetic Sequence

I did this question with on of my year 11 students. I think the algebra and the subscripts can be a bit tricky.

If

and

, then prove that

. Here where

and

are terms of an arithmetic sequence.

Mathematics Methods Units 1&2 – Exercise 15B Question 19

(1) And if (2) Subtract equation (3) Therefore Substitute (4) Therefore (5) Substitute (6) |

As you can see from equation ![]()

Filed under Algebra, Arithmetic, Sequences, Year 11 Mathematical Methods