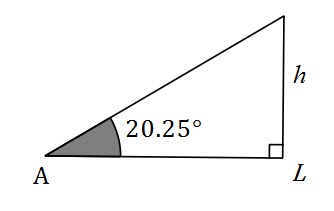

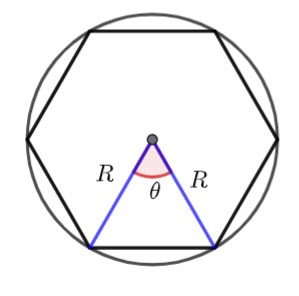

Solve ![]() for

for ![]()

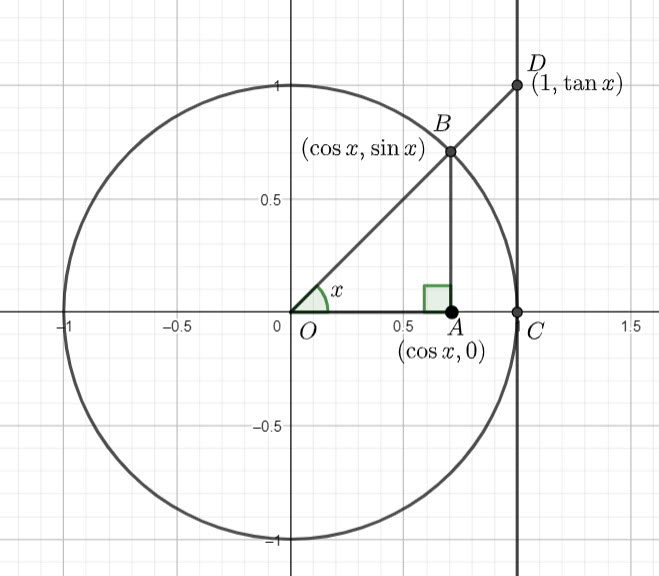

Sine is positive in the first and second quadrants.

![]()

![]()

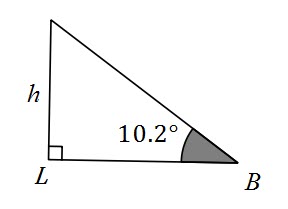

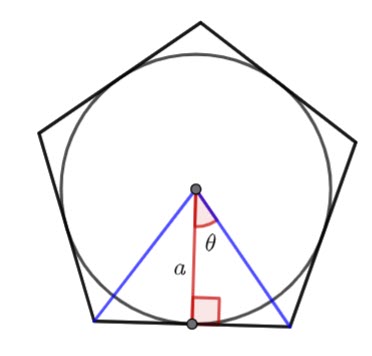

But what if we aren’t given a domain for the ![]() values?

values?

Then we need to give general solutions.

For example,

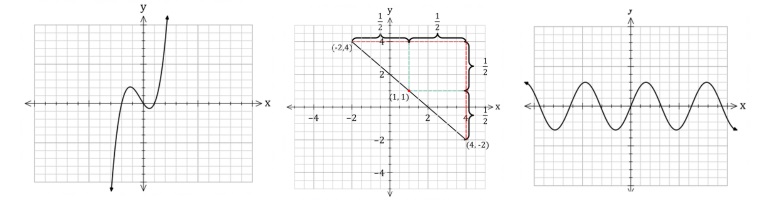

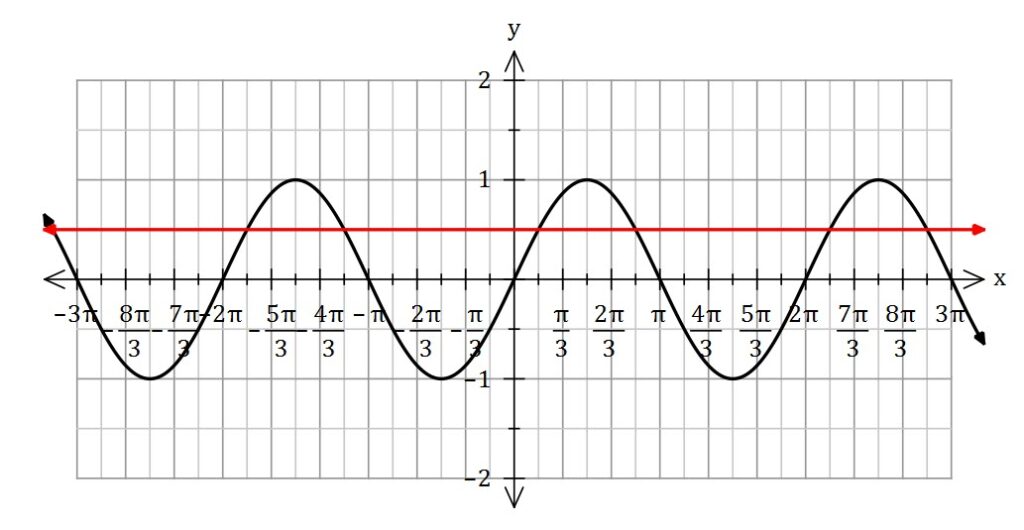

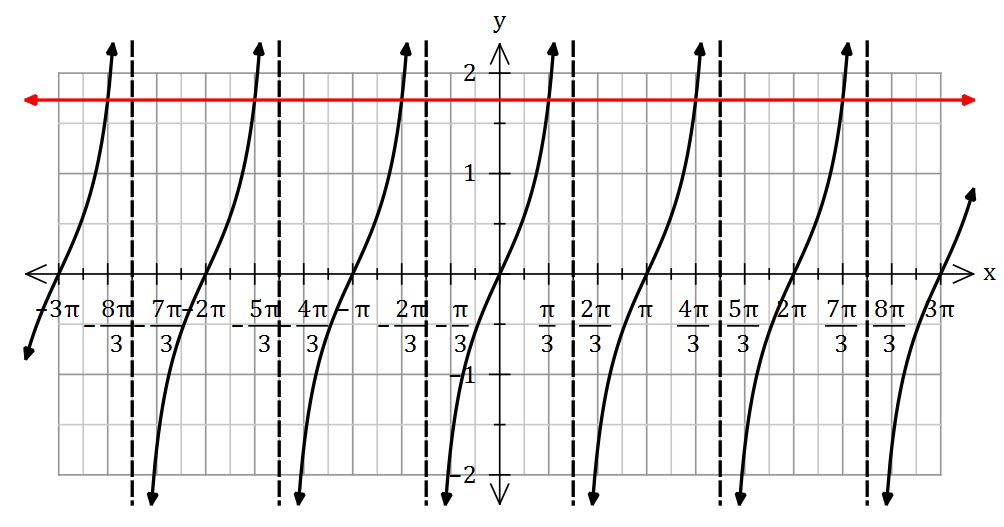

Solve ![]()

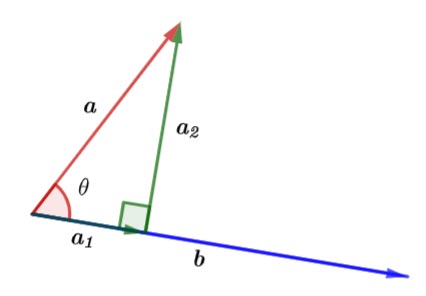

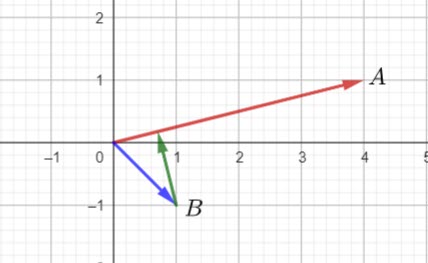

As you can see from the sketch above, there are infinite solutions.

The sine function has a period of ![]() , and so if

, and so if ![]() is a solution then

is a solution then ![]() is also a solution. This means

is also a solution. This means ![]() is a general solution. And we can do the same for the second solution

is a general solution. And we can do the same for the second solution ![]() .

.

In general

We can turn this into one equation

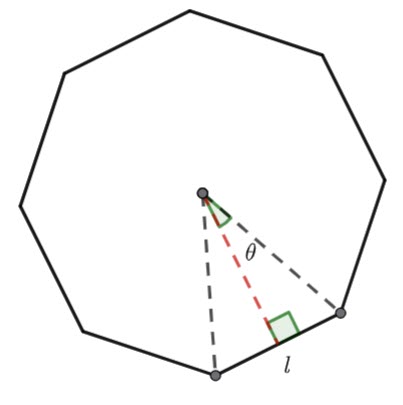

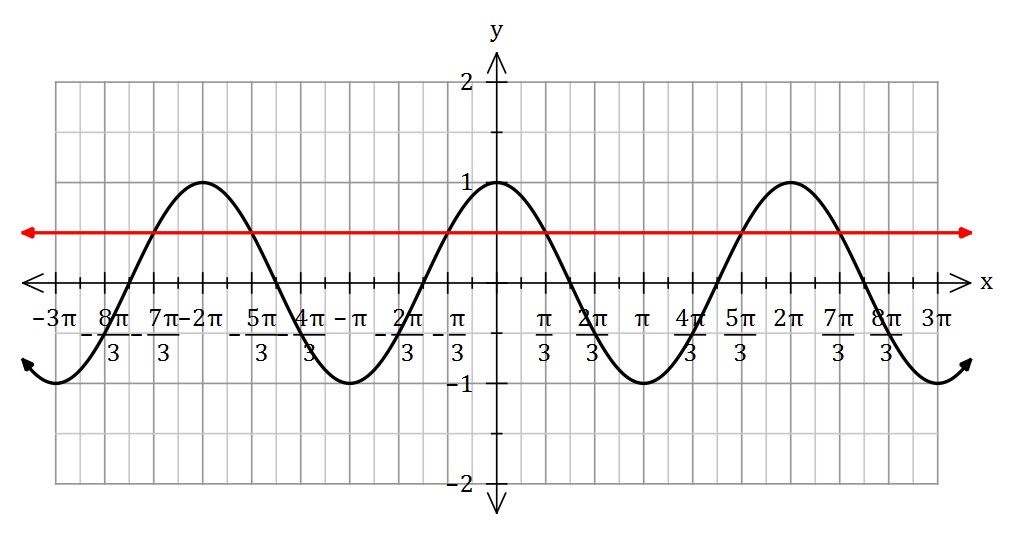

What about cosine?

Solve ![]()

Cosine is positive in the first and fourth quadrants (it also has a period of ![]() . The first two (positive) solutions are

. The first two (positive) solutions are ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

To generalise, ![]() , which we can make into one equation

, which we can make into one equation ![]()

In general

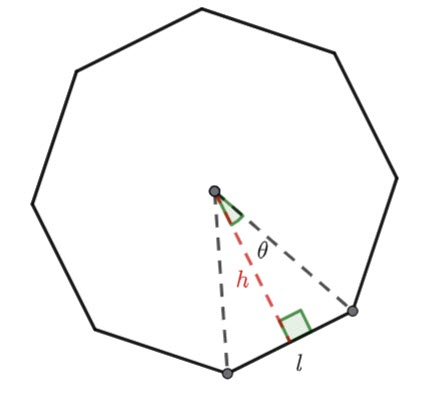

What about the tangent function? Remember tan has a period of ![]() .

.

Solve ![]()

First, note that the solutions are all a common distance (![]() ) apart.

) apart.

Tan is positive in the first and the third quadrant

![]()

![]()

Because all of the solutions are ![]() radians apart, the general solution is

radians apart, the general solution is ![]()

In general

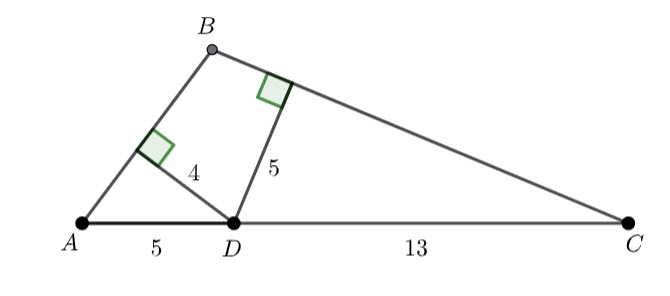

Examples

Solve for all values of ![]() ,

, ![]()

![]()

This is a quadratic equation – we need two numbers that add to ![]() and multiple to

and multiple to ![]() ,

, ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

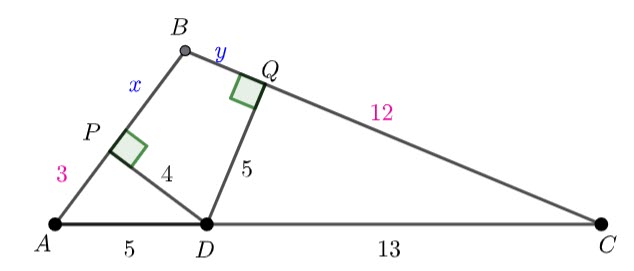

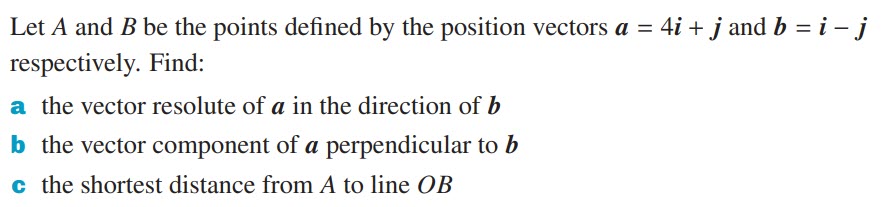

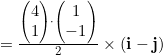

Solve ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()