I usually choose to use synthetic division when factorising polynomials, but I know some teachers are unhappy when their students do this. So for completeness, here is my PDF for Polynomial Long Division.

Category Archives: Quadratics

Completing the Square

Completing the square is useful to

- sketch parabolas.

- solve quadratics.

- factorising quadratics

- finding the centre and radius version of the equation of a circle.

When completing the square we take advantage of perfect squares. For example, ![]()

![]() and

and ![]()

Example 1

Put ![]() into completed square form.

into completed square form.

What perfect square has an ![]() term?

term?

![]()

We don’t want ![]() , we want

, we want ![]() , so subtract

, so subtract ![]()

![]()

![]()

What about a non-monic quadratic? For example,

![]()

Factorise the ![]()

![]()

And continue as before

![]()

Example 2

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Hard Equation Solving Question

Find the value(s) of ![]() such that the equation below has two numerically equal but opposite sign solutions (e.g.

such that the equation below has two numerically equal but opposite sign solutions (e.g. ![]() and

and ![]() ).

).

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

For there to be two numerically equal but opposite sign solutions, the ![]() term of the quadratic equation must be

term of the quadratic equation must be ![]() .

.

![]()

Hence ![]() .

.

When ![]() the equation becomes

the equation becomes

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Filed under Algebra, Polynomials, Quadratic, Quadratics, Solving, Solving, Solving Equations

Trigonometric Exact Values

Find exactly ![]()

We must be able to find an arithmetic combination of the exact values we knew to find ![]() .

.

![]()

![]()

I re-arranged as above, so I could take advantage of ![]() and

and ![]()

| Useful identities |

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Hence,

![]()

![]()

![]()

Use the quadratic equation formula

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

As ![]() ,

, ![]()

Factorising Non-Monic Quadratics

The general equation of a quadratic is ![]()

Let’s explore different methods of factorising a non-monic quadratic (the ![]() term is not

term is not ![]() )

)

Factorise ![]()

We need to find two numbers that add to ![]() and multiply to

and multiply to ![]() (i.e. add to

(i.e. add to ![]() and multiply to

and multiply to ![]()

The two numbers are ![]() and

and ![]()

Method 1 – Splitting the middle term

This is the method I teach the most often

![]()

Split the middle term (the ![]() term) into the two numbers

term) into the two numbers

![]()

The order doesn’t matter.

Find a common factor for the first term terms, and then for the last two terms.

![]()

There is a common factor of ![]() , factor it out.

, factor it out.

![]()

Method two – Fraction

![]()

Put ![]() into both factors and divide by

into both factors and divide by ![]()

![]()

Factorise

![]()

![]()

![]()

Method 3 – Monic to non-monic

![]()

Multiply both sides of the equation by ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Let ![]()

![]()

Factorise

![]()

Replace the ![]() with

with ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

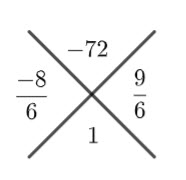

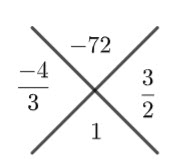

Method 4 – Cross Method

![]()

Place the two numbers in the cross

Place the two numbers that add to ![]() and multiply to

and multiply to ![]() in the other parts of the cross.

in the other parts of the cross.

Divide these two numbers by ![]() (i.e

(i.e ![]() )

)

Simplify

Hence,

![]()

Which is

![]()

Method 5 – By Inspection

This is my least favourite method – although students get better with practice

![]()

The factors of ![]() are

are ![]() and

and ![]() and the factors of

and the factors of ![]() are

are ![]()

We know one number is positive and one number negative.

Which give us all of these possibilities

| Possible factorisations | ||

| No | ||

| No | ||

| No | ||

| No | ||

| No | ||

| Almost, switch the signs | ||

| Yes |

![]()

With a bit of practice you don’t need to check all of the possibilties, but I find students struggle with this method.

Method 6 – Grid

![]()

Create a grid like the one below

Find the two numbers that multiply to ![]() and add to

and add to ![]() and place them in the other grid spots (see below)

and place them in the other grid spots (see below)

Find the HCF (highest common factor) of each row and put in the first column.

Row ![]() HCF=

HCF=![]() , Row

, Row ![]() HCF=

HCF=![]()

For the columns, calculate what is required to multiple the HCF to get the table entry.

For example, what do you need to multiple ![]() and

and ![]() by to get

by to get ![]() and

and ![]() ? In this case it is

? In this case it is ![]() . It’s always going to be the same thing, so just use one value to calculate it,

. It’s always going to be the same thing, so just use one value to calculate it,

The factors are column ![]() and row

and row ![]()

![]()

The two methods I use the most are splitting the middle term, and the cross method, but I can see value in the grid method.

Filed under Algebra, Factorising, Factorising, Polynomials, Quadratic, Quadratics

Problem Solving

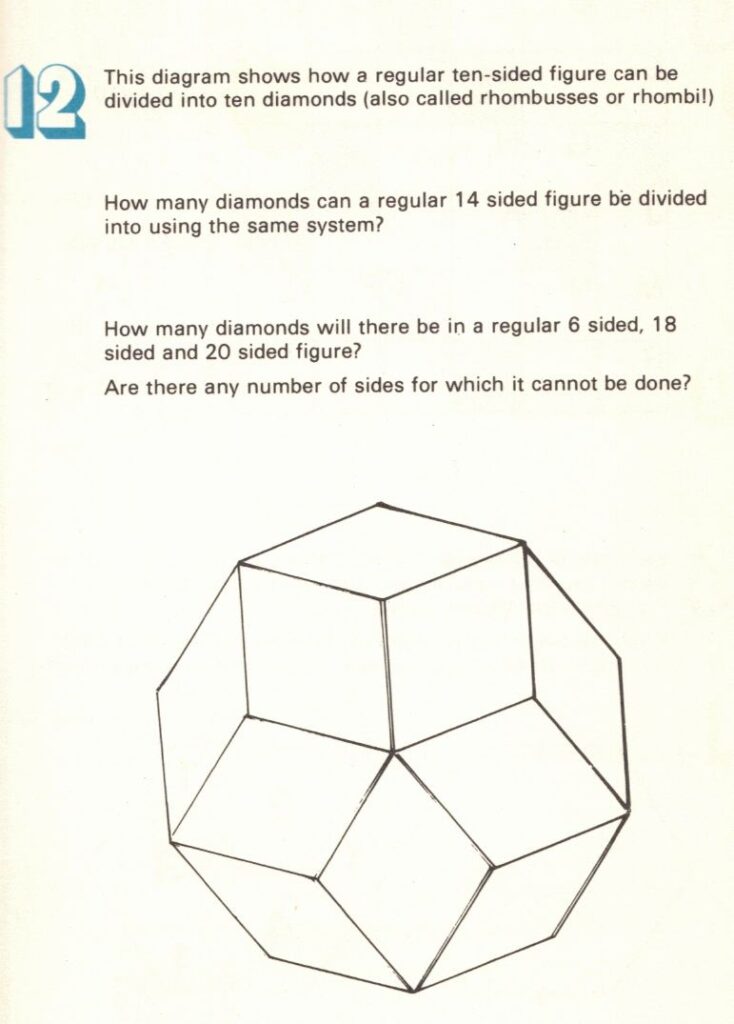

I am came across this problem and was fascinated. It’s from this book

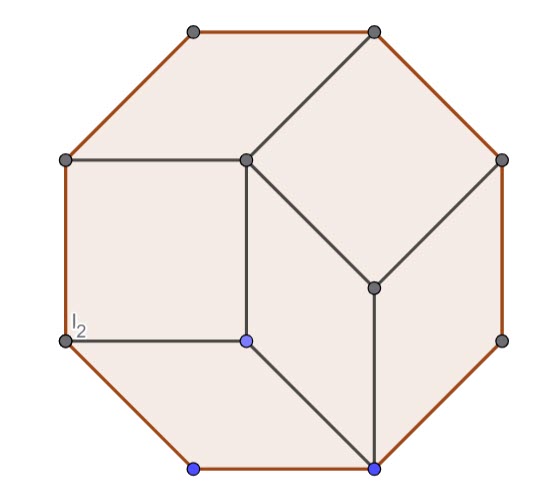

At first I went straight to the 14-sided polygon, and tried to draw the diamonds (parallelograms), but then I thought let’s start smaller and see if there is a pattern.

Clearly a square contains 1 diamond (itself).

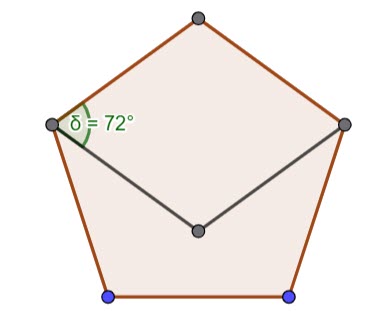

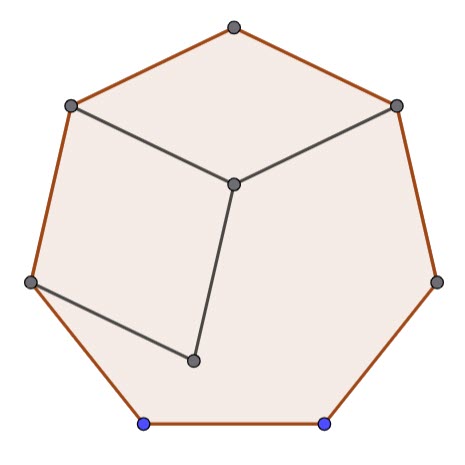

Pentagon

It’s not possible with a pentagon.

Hexagon

A hexagon has 6 diamonds

Septagon

I am guessing it’s not possible to fill a regular 7-sided shape with diamonds

It’s not possible with odd numbers of sides. Regular polygons with an odd number of sides have no parallel sides, so we can’t cover it with rhombi (which have opposite sides parallel).

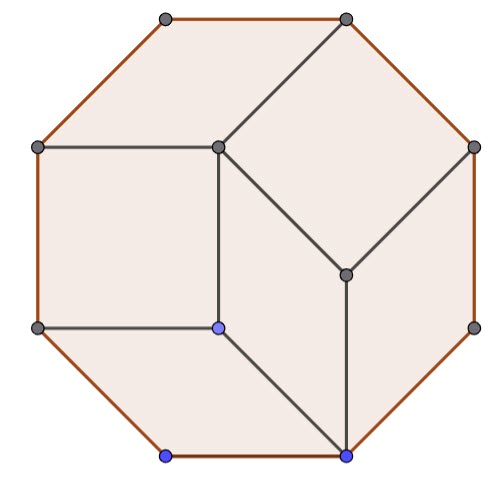

Octagon

An octagon has 6 diamonds.

We know a decoagon has 10 diamonds (from the question)

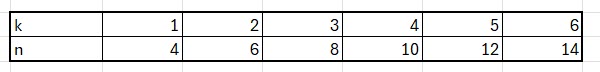

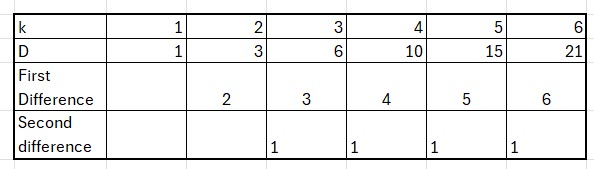

Let’s put together what we know

| Diamonds |

These are the triangular numbers, so when ![]() the number of diamonds is

the number of diamonds is ![]() , and for

, and for ![]() it’s

it’s ![]() .

.

We can work out a rule for calculating the number of diamonds given the number of sides.

Because the difference in the ![]() values is not

values is not ![]() , I am going to get

, I am going to get ![]() and

and ![]() in terms of

in terms of ![]() and then combine the two equations.

and then combine the two equations.

From the above table, ![]()

We know this rule is quadratic as the second difference is constant, hence

![]()

![]()

(1) ![]()

![]()

(2) ![]()

Solve simultaneously, subtract equation ![]() from equation

from equation ![]()

(3) ![]()

Substitute for ![]() into equation

into equation ![]()

![]()

![]() , therefore

, therefore ![]()

We know ![]() hence

hence ![]()

Hence ![]()

![]()

![]()

Let’s test our rule for ![]()

![]()

Filed under Area, Geometry, Interesting Mathematics, Puzzles, Quadratics

Deriving the Quadratic Equation formula

My year 10 students have been learning how to complete the square with the idea of then deriving the quadratic equation formula.

The general equation for a quadratic is ![]()

Completing the square,

![]()

Factorise out the leading coefficient (i.e. ![]() )

)

![]()

Half the second term (i.e ![]() ) and subtract the square of the second term.

) and subtract the square of the second term.

![]()

![]()

Simplify

![]()

![]()

![]()

Now let’s solve

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Which is the quadratic equation formula.

Filed under Algebra, Quadratic, Quadratics, Solving, Solving, Solving Equations

Interesting Equation

I think this one is doing the rounds, I first saw it here.

![]()

![]() is the obvious answer,

is the obvious answer, ![]() , but are there more answers?

, but are there more answers?

This was my approach

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

A quadratic equation.

Hence,

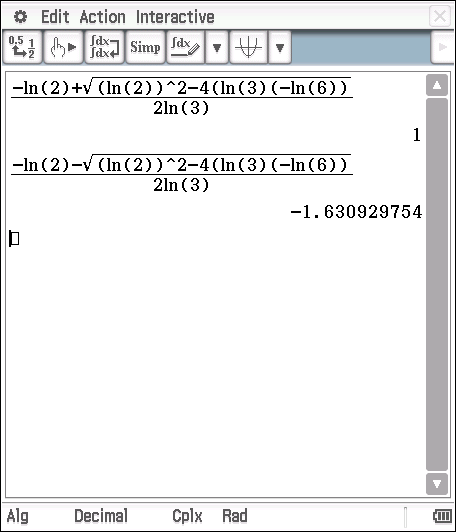

![]()

I then used my calculator

Hence ![]() 0r

0r ![]()

Filed under Algebra, Index Laws, Interesting Mathematics, Quadratics, Solving

Quadratic Rule from a Table of Values

How do you find a quadratic rule from a table of values?

For example,

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 0 | 6 | 14 | 24 |

Find the first difference

| First Difference | 6-0=6 | 14-6=8 | 24-14=10 |

Find the second difference (if the second difference is a constant, then it is quadratic)

| Second Difference | 8-6=2 | 10-8=2 |

The general equation of a quadratic is ![]()

The second difference is ![]()

Hence our equation is now ![]()

The ![]() value is the vertical intercept (

value is the vertical intercept (![]() ). We can back track in the table

). We can back track in the table

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 0 | 6 | 14 | 24 |

As the first differences are 6, 8, 10, the one between 0 and 1 must be 4

![]()

![]()

Our equation is now ![]() .

.

We can now use any other point to find the ![]() value.

value.

Let’s use the point ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The function is ![]()

Let’s try another one

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 17 | 31 | 49 |

First differences

| First difference | 10 | 14 | 18 |

Second difference

| Second Difference | 4 | 4 |

Hence ![]() , therefore

, therefore ![]()

The equation is now ![]()

Instead of back tracking, this time I am going to use two points and simultaneous equations.

Using points ![]() and

and ![]()

![]()

(1) ![]()

![]()

(2) ![]()

Equation 2 – Equation 1

![]()

Substitute ![]() into equation 1

into equation 1

![]()

![]()

![]()

Hence the equation is ![]()

Filed under Quadratics, Uncategorized